Maybe you’ve been part of a team that you’ve seen slowly slide into a rut. You didn’t notice it happen, but you’re now not shipping anything, no one’s talking to each other, and the management’s Eye of Sauron has cast its gaze upon you.

Maybe you’ve just joined a team that’s in the doldrums.

Maybe the people who used to oil the wheels that kept everyone together have moved on and you’re having to face facts—you all hate each other.

However you’ve ended up in this situation, the fact is that you’re now here and it’s up to someone to do something about it. And that person might be you.

You’re not alone#section2

The first thing to understand is that you’re not the only person to ever encounter problems. Things like this happen all the time at work, but there are simple steps you can take and habits you can form to ease the situation and even dig yourself (and your team) out of the hole. I’ll share some techniques that have helped me, and maybe they can work for you, too.

So let me tell you a story about a hot mess I found myself in and how we turned it around. Names and details have been changed to protect the innocent.

It always starts out great#section3

An engineer called Jen was working with me on a new feature on our product that lets people create new meal recipes themselves. I was the Project Manager. We were working in six-week cycles.

She had to rely on an API that was managed by Tom (who was in another team) to allow her to get and set the new recipe information on a central database. Before we kicked off, everyone knew the overall objective and everyone was all smiles and ready to go.

The system architecture was a legacy mishmash of different parts of local databases and API endpoints. And, no prizes for guessing what’s coming next, the API documentation was like Swiss cheese.

Two weeks into a six-week cycle, Jen hit Tom up with a list of her dream API calls that she wanted to use to build her feature. She asked him to confirm or deny they would work—or even if they existed at all—because once she started digging into the docs, it wasn’t clear to her if the API could support her plans.

However, Tom had form for sticking his head in the sand and not responding to requests he didn’t like. Tom went to ground and didn’t respond. Tom’s manager, Frankie, was stretched too thin, and hence wasn’t paying attention to this until I was persistently asking about it, in increasingly fraught tones.

In the meantime, Jen tried to do as much as she could. Every day she built a bit more based on her as-yet unapproved design, hoping it would all work out.

With two weeks left to go, Tom eventually responded with a short answer—which boiled down to “The API doesn’t support these calls and I don’t see why I should build something that does. Why don’t you get the data from the other part of the system? And by the way, if I’m forced to do this, it will take at least six weeks.”

And as we know, six weeks into two weeks doesn’t go. Problem.

How did we sort it?

Step 1 — Accept#section4

When things go south, what do you do?

Accept it.

Acknowledge whatever has happened to get you into this predicament. Take some notes about it to use in team appraisals and retrospectives. Take a long hard look at yourself, too.

Write a concise, impersonal summary of where you are. Try not to write it from your point of view. Imagine that you’re in your boss’ seat and just give them the facts as they are. Don’t dress things up to make them sound better. Don’t over-exaggerate the bad. Leave the emotions to the side.

When you can see your situation clearly, you’ll make better decisions.

Now, pointing out the importance of taking some time to cool down and gather your thoughts seems obvious, but it’s based on the study of some of the most basic circuitry in our brains. Daniel Goleman’s 1995 book, Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ, introduces the concept of emotional hijacking; the idea that the part of our brain that deals with emotion—the limbic system—can biologically interrupt rational thinking when it is overstimulated. For instance, experiments show that the angrier men get, the poorer are the decisions they make at the casino. And another study found that people in a negative emotional state are more likely to deviate from logical norms. To put it another way, if you’re pissed off, you can’t think straight.

So when you are facing up to the facts, avoid the temptation to keep it off-the-record and only discuss it on the telephone or in person with your colleagues. There’s nothing to be scared of by writing it down. If it turns out that you’re wrong about something, you can always admit it and update your notes. If you don’t write it down, then there’s always scope for misunderstanding or misremembering in future.

In our case, we summarized how we’d ended up at that juncture; the salient points were:

- I hadn’t checked to ensure we had scoped it properly before committing to the work. It wasn’t a surprise that the API coverage was patchy, but I turned a blind eye because we were excited about the new feature.

- Jen should have looked for the hard problem first rather than do a couple of weeks’ worth of nice, easy work around the edges. That’s why we lost two weeks off the top.

- Tom and Frankie’s communication was poor. The reasons for that don’t form part of this discussion, but something wasn’t right in that team.

And that’s step one.

Step 2 — Rejoice#section5

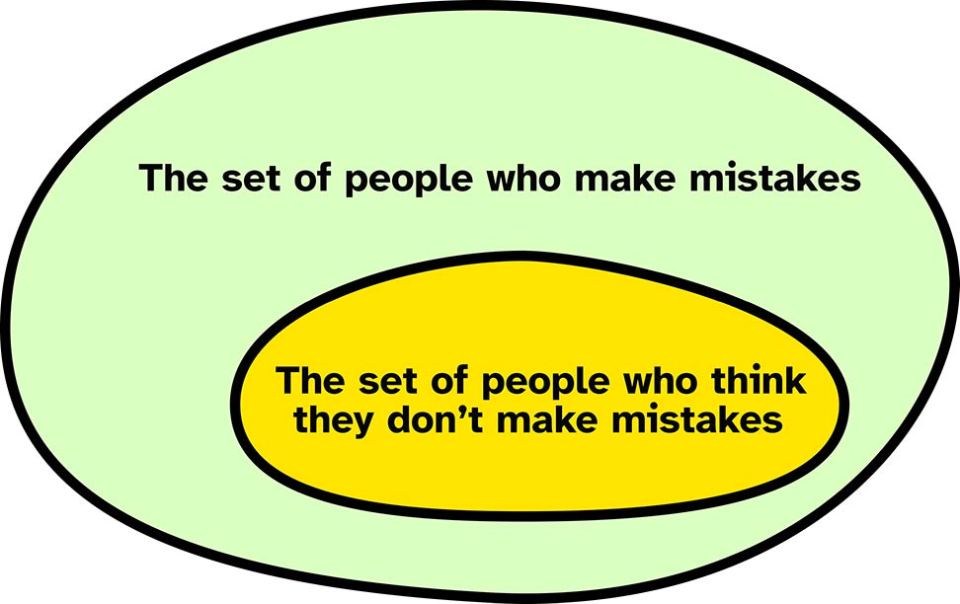

Few people like to make mistakes, but everyone will make one at some point in their life. Big ones, small ones, important ones, silly ones—we all do it. Don’t beat yourself up.

At the start of my career, I worked on a team whose manager had a very high opinion of himself. He was good, but what I learned from him was that he spread that confidence around the team. If something was looking shaky, he insisted that if we could “smell smoke,” that he had to be the first to know so he could do something about it. If we made a mistake, there was no hiding from it. We learned how to face up to it and accept responsibility, but what was more important was learning from him the feeling we were the best people to fix it.

There was no holding of grudges. What was done, was done. It was all about putting it behind us.

He would tell us that we were only in this team because he had handpicked us because we were the best and he only wanted the best around him. Now, that might all have been manipulative nonsense, but it worked.

The only thing you can control is what you do now, so try not to fret about what happened in the past or get anxious about what might happen in the future.

With that in mind, once you’ve written the summary of your sticky situation, set it aside!

I’ll let you in on a secret. No one else is interested in how you got here. They might be asking you about it (probably because they are scared that someone will ask them), but they’re always going to be more interested in how you’re going to sort the problem out.

So don’t waste time pointing fingers. Don’t prepare slide decks to throw someone under the bus. Tag that advice with a more general “don’t be an asshole” rule.

If you’re getting consistent heat about the past, it’s because you’re not doing a good enough job filling the bandwidth with a solid, robust, and realistic plan for getting out of the mess.

So focus on the future.

Sometimes it’s not easy to do that, but remember that none of this is permanent. Trust in the fact that if you pull it together, you’ll be in a much more powerful position to decide what to do next.

Maybe the team will hold together with a new culture or, if it is irretrievably broken, once you’re out of the hole then you can do something about it and switch teams or even switch jobs. But be the person who sorted it out, or at the very least, be part of the gang who sorted it out. That will be obvious to outsiders and makes for a much better interview question response.

In our story with Jen, we had a short ten-minute call with everyone involved on the line. We read out the summary and asked if anyone had anything to add.

Tom spoke up and said that he never gets time to update the API documentation because he always has to work on emergencies. We added that to our summary:

- Tom has an ongoing time management problem. He doesn’t have enough time allocated to maintain and improve the API documentation.

After that was added, everyone agreed that the summary was accurate.

I explained that the worst thing that could now happen was that we had to report back to the wider business that we’d messed up and couldn’t hit our deadline.

If we did that, we’d lose face. There would be real financial consequences. It would show up on our appraisals. It wouldn’t be good. It wouldn’t be the end of the world, but it wasn’t something that we wanted. Everyone probably knew all that already, but there’s a power in saying it out loud. Suddenly, it doesn’t seem so scary.

Jen spoke up to say that she was new here and really didn’t want to start out like this. There was some murmuring in general support. I wrapped up that part of the discussion.

I purposefully didn’t enter into a discussion about the solution yet. We had all come together to admit the circumstances we were in. We’d done that. It was enough for now.

Step 3 — Move on#section6

Stepping back for a second, as the person who is going to lead the team out of the wilderness, you may want to start getting in everyone’s face. You’ll be tempted to rely on your unlimited reserves of personal charm or enthusiasm to vibe everyone up. Resist the urge! Don’t do it!

Your job is to give people the space to let them do their best work.

I learned this the hard way. I’m lucky enough that I can bounce back quickly, but when someone is under pressure, funnily enough, a super-positive person who wants to throw the curtains open and talk about what a wonderful day it is might not be the most motivational person to be around. I’ve unwittingly walked into some short-tempered conversations that way.

Don’t micromanage. In fact, scrap all of your management tricks. Your job is to listen to what people are telling you—even if they’re telling you things by not talking.

Reframe the current problem. Break it up into manageable chunks.

The first task to add to your list of things to do is simply to “Decide what we’re going to do about [the thing].”

It’s likely that there’s a nasty old JIRA ticket that everyone has been avoiding or has been bounced back and forth between different team members. Set that aside. There’s too much emotional content invested in that ticket now.

Create a new task that’s entirely centered on making a decision. Now, break it down into subtasks for each member of the team, like “Submit a proposal for what to do next.” Put your own suggestions in the mix but do your best to dissociate yourself from them.

Once you start getting some suggestions back and can tick those tasks off the list, you start to generate positive momentum. Nurture that.

If a plan emerges, champion it. Be wary of naysayers. Challenge them respectfully with “How do you think we should…?” questions. If they have a better idea, champion that instead; if they don’t respond at all, then gently suggest “Maybe we should go with this if no one else has a better idea.”

Avoid words like “need,” “just,” “one,” or “small.” Basically, anything that imposes a view of other people’s work. It seems trivial, but try to see it from the other side.

Saying, “I just need you to change that one small thing” hits the morale-killing jackpot. It unthinkingly diminishes someone else’s efforts. An engineer or a designer could reasonably react by thinking “What do you know about how to do this?!” Your job is to help everyone drop their guard and feel safe enough to contribute.

Instead, try “We’re all looking at you here because you’re good at this and this is a nasty problem. Maybe you know a way to make this part work?”

More often than not, people want to help.

So I asked Jen, Tom, and Frankie to submit their proposals for a way through the mess.

It wasn’t straightforward. Just because we’d all agreed how we got here didn’t just magically make all the problems disappear. Tom was still digging his heels in about not wanting to write more code, and kept pushing back on Jen.

There was a certain amount of back and forth. Although, with some constant reminders that we should maybe focus on what will move us forward, we eventually settled on a plan.

Like most compromises, it wasn’t pretty or simple. Jen was going to have to rely on using the local database for a certain amount of the lower-priority features. Tom was going to have to create some additional API functions and would end up with some unnecessary traffic that might create too much load on the API.

And even with the compromise, Tom wouldn’t be finished in time. He’d need another couple of weeks.

But it was a plan!

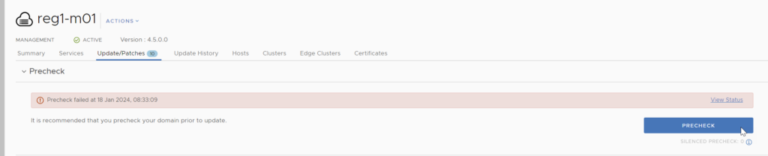

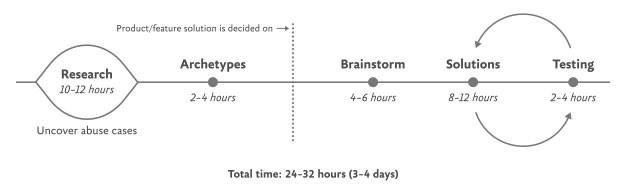

N.B. Estimating is a whole other subject that I won’t cover here. Check out the Shape Up process for some great advice on that.

Step 4 — Spread the word#section7

Once you’ve got a plan, commit to it and tell everyone affected what’s going on.

When communicating with people who are depending on you, take the last line of your email, which usually contains the summary or the “ask,” and put it at the top. When your recipient reads the message, the opener is the meat. Good news or bad news, that’s what they’re interested in. They’ll read on if they want more.

If it’s bad news, set someone up for it with a simple “I’m sorry to say I’ve got bad news” before you break it to them. No matter who they are, kindly framing the conversation will help them digest it.

When discussing it with the team, put the plan somewhere everyone can see it. Transparency is key.

Don’t pull any moves—like publishing deadline dates to the team that are two weeks earlier than the date you’ve told the business. Teams aren’t stupid. They’ll know that’s what you do.

Publish the new deadlines in a place where everyone on the team can see them, and say we’re aiming for this date but we’re telling the business that we’ll definitely be done by that date.

In our case, I posted an update to the rest of the business as part of our normal weekly reporting cycle to announce we’d hit a bump that was going to affect our end date.

Here’s an extract:

Hi everyone,

Here’s the update for the week. I’m afraid there’s a bit of bad news to start but there is some good news too.

First:

We uncovered a misunderstanding between Jen and Tom this week. The outcome is that Tom has more API work to do than he anticipated. This affects the delivery date and means we’re now planning to finish 10 working days later on November 22.

**Expected completion date ** CHANGED ****

Original estimate: November 8

Current estimate: November 22Second:

We successfully released version 1.3 of the app into the App Store 🎉.

And so on…

That post was available for everyone within the team to see. Everyone knew what was to be done and what the target was.

I had to field some questions from above, but I was ready with my summary of what went wrong and what we’d all agreed to do as a course of action. All I had to do was refer to it. Then I could focus on sharing the plan.

And all manner of things shall be well#section8

Now, I’d like to say that we then had tea and scones every day for the next month and it was all rather spiffing. But that would be a lie.

There was some more wailing and gnashing of teeth, but we all got through it and—even though we tried to finish early but failed—we did manage to finish by the November 22 date.

And then, after a bit of a tidy up, we all moved on to the next project, a bit older and a bit wiser. I hope that helps you if you’re in a similar scenario. Send me a tweet or email me at liam.nugent@hey.com with any questions or comments. I’d love to hear about your techniques and advice.